After a few years of back-and-forth in Sacramento, California lawmakers and the governor really did what they've been talking about doing. They've ended single-family zoning statewide.

After a few years of back-and-forth in Sacramento, California lawmakers and the governor really did what they've been talking about doing. They've ended single-family zoning statewide.

Cities now must allow multiple units to be built, even where current zoning states that only single-family residences are permitted.

However, nothing changes overnight, and no one is forced to build or demolish anything.

There's more to it all, lots of details to discern, several relevant limitations and great uncertainty about the impact.

But one thing is certain: It's the law.

Here's a first dive into the issues, with a swipe at the question of "what does this mean for Manhattan Beach real estate?"

Background

The state can't house everyone who lives here or wants to live here. State officials projected 3 years ago that California would need 1.8 million new homes by 2025, but said the state produces only about 80,000 new units per year. At that pace, it would take 23 years to meet the projected need. Other estimates of housing run from half that figure, around 800,000 units, to roughly double, 3.5 million units needed.

The state is trying to force cities to make way and add housing. Among the bigger steps by the state to encourage more housing before this year:

The state is trying to force cities to make way and add housing. Among the bigger steps by the state to encourage more housing before this year:

Pressuring cities to meet housing targets. A regular multi-year planning process known as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment makes suggestions for cities and regions as to how many new housing units are needed. In 2017, a new law (SB 35) threatened cities that don't meet their targets by allowing for more housing, including affordable housing, with a forced-approval process down the road for new development. The gist: Accommodate more building now, or the state will force cities to allow big new housing projects later.

Requiring OKs for ADUs. Cities are now effectively required to allow ADUs ("accessory dwelling units") to be constructed on existing properties, including a new secondary building on a single-family lot, garage conversion at a home or multi-unit building, and more. Cities like Manhattan Beach that have used regulations, such as minimum parking requirements, to deter or prevent ADUs now must make accommodations to allow them instead.

Requiring OKs for ADUs. Cities are now effectively required to allow ADUs ("accessory dwelling units") to be constructed on existing properties, including a new secondary building on a single-family lot, garage conversion at a home or multi-unit building, and more. Cities like Manhattan Beach that have used regulations, such as minimum parking requirements, to deter or prevent ADUs now must make accommodations to allow them instead.

Preventing demolitions/new builds that reduce the number of units. Cities must make sure that new construction does not result in fewer individual housing units than were present on a site at the time of demolition, under SB 330 (Housing Crisis Act, 2019). For instance, a dated duplex in Manhattan Beach down by the beach can't be knocked down and rebuilt as an SFR, but must include a second unit. The purportedly temporary restriction runs from 2020 till Jan. 1, 2025. Want to bet that will be extended?

This Year's Bills

SB 9 and SB 10 are the main housing-related bills getting all the headlines, and deservedly so.

SB 9, sometimes known as the "duplex bill," applies to urban areas including much of L.A. county and Manhattan Beach. It allows many homeowners to build a second unit on an existing lot. While this is consistent with the state's newer pro-ADU policy, ADUs are, by definition, junior units. Now an owner can build an equal or greater second unit, which typically would have required R2 zoning previously.

What's more, an owner could split their lot and both lots could contain 2 units, provided that the resulting split lots meet a minimum size (1,200 sqft. each).

This raises the prospect of a single lot with one home today becoming 4 units tomorrow, a fairly jarring change in a neighborhood characterized by one-on-a-lot development like is typical in most districts of Manhattan Beach.

SB 10 is a different bird, meant to help cities that want to approve housing developments with up to 10 units by ditching environmental reviews under the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA. The focus of the bill appears to be on speeding affordable housing development in "transit-rich" urban areas. It's hard to say today how this might impact Manhattan Beach, but never say never.

Limitations of SB 9

• An owner who adds units and/or splits the lots must commit to living in one of the units for 3 years.

• Units that have served as rentals within the prior 3 years cannot be redeveloped with benefit of these new rules.

• Designated historic districts are exempt from this form of new development.

• Cities can require 1 off-street parking spot per unit, unless the property is deemed to be within a half mile of public transit.

• Newly built units can't be short-term rentals.

First Hints of Local Impact in Manhattan Beach

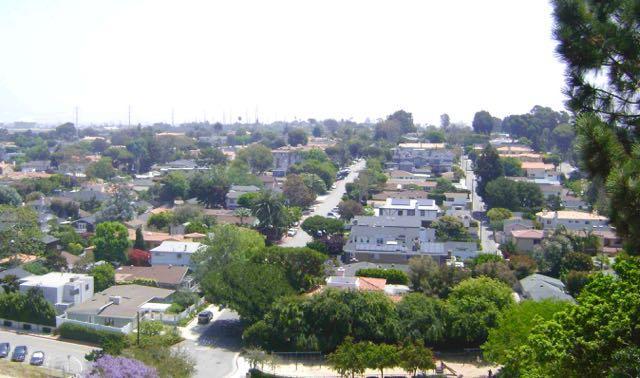

The city's existing zoning already favors density closer to the beach and major roads (especially MB Blvd.). The state now wants homeowners to be the vanguard of even greater density citywide, albeit without the deliberate planning that zoning is meant to represent. How is this going to play out?

Just 5%? The most widely quoted expert analysis of SB 9, by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, estimates that only 5.4% of single-family lots in California would pencil out to be worth redeveloping under SB 9 rules.

If you don't like the sound of 4-plexes replacing SFRs all over town, you might view that as reassuring, if ~95% of single-family lots would not be redeveloped.

If you don't like the sound of 4-plexes replacing SFRs all over town, you might view that as reassuring, if ~95% of single-family lots would not be redeveloped.

(USPS counts about 14,000 residential addresses in MB, but that includes duplexes and multi-family units. We'll work on getting a count of SFR lots.)

Of course, any dense redevelopment could still be shocking to any given block or set of neighbors. About 5% means about 1 in 20 SFRs in town, potentially.

Owners-only obstacle. Possibly the greatest limitation on development in SB 9 is the bar to speculators, meaning the legislation's requirement for an owner to live in a redeveloped property for 3 years. No, we have no idea yet how that's going to be enforced, but you certainly won't see a spec builder bellying up to the permit desk and securing approvals for a 4-plex on a leafy street in the Tree Section.

No replacing rentals with density. The restriction on developing past rentals also raises a further obstacle. If you consider that the housing most likely to be redeveloped under any set of laws is going to be older, smaller, obsolete structures, then you see the issue. Very often, such dated properties become long-term rentals after the owners move out and hold onto the properties for years on end. Any home rented within 3 years prior to a development application can't be redeveloped using SB 9's new rules for greater density. (SB 9 does not appear to prevent redevelopment overall.)

No parking? It will be very interesting to see how the "parking loophole" in SB 9 works within Manhattan Beach. If you've ever tried to build here, you know how requirements for on-site parking (covered and/or uncovered) can squeeze development plans. The state's prior ADU rules chipped away at parking requirements that had been a barrier to adding units. Can SB 9 really mean new, denser developments require only one space per unit, or none if within a half mile of "public transit?" Heck, the city's only 2 miles square, and people do actually have cars.

No parking? It will be very interesting to see how the "parking loophole" in SB 9 works within Manhattan Beach. If you've ever tried to build here, you know how requirements for on-site parking (covered and/or uncovered) can squeeze development plans. The state's prior ADU rules chipped away at parking requirements that had been a barrier to adding units. Can SB 9 really mean new, denser developments require only one space per unit, or none if within a half mile of "public transit?" Heck, the city's only 2 miles square, and people do actually have cars.

City under pressure to add, regardless. Efforts to add more housing units within the city aren't going to be restricted to SB 9 projects, however.

The latest Regional Housing Needs Assessment process declared that Manhattan Beach must make way to add 791 units by 2029. It's a figure that then-mayor Nancy Hersman called "staggering," commenting, "I don’t know anyone who can look at Manhattan Beach and imagine 791 housing units."

The state is trying, for now, to use a combination of bending rules and market forces to encourage denser new development. But the city could also face new mandates if (when?) it falls short of the 2029 targets.

-----------------------------------------------------

We'll come back to this topic as more info develops, and to address any questions or errors.

To address a specific question to us now, email Dave (address: dave [ at ] edge-rea.com),

After a few years of back-and-forth in Sacramento, California lawmakers and the governor really did what they've been talking about doing. They've ended single-family zoning statewide.

After a few years of back-and-forth in Sacramento, California lawmakers and the governor really did what they've been talking about doing. They've ended single-family zoning statewide.

The state is trying to force cities to make way and add housing. Among the bigger steps by the state to encourage more housing before this year:

The state is trying to force cities to make way and add housing. Among the bigger steps by the state to encourage more housing before this year: Requiring OKs for ADUs. Cities are now effectively required to allow ADUs ("accessory dwelling units") to be constructed on existing properties, including a new secondary building on a single-family lot, garage conversion at a home or multi-unit building, and more. Cities like Manhattan Beach that have used regulations, such as minimum parking requirements, to deter or prevent ADUs now must make accommodations to allow them instead.

Requiring OKs for ADUs. Cities are now effectively required to allow ADUs ("accessory dwelling units") to be constructed on existing properties, including a new secondary building on a single-family lot, garage conversion at a home or multi-unit building, and more. Cities like Manhattan Beach that have used regulations, such as minimum parking requirements, to deter or prevent ADUs now must make accommodations to allow them instead. If you don't like the sound of 4-plexes replacing SFRs all over town, you might view that as reassuring, if ~95% of single-family lots would not be redeveloped.

If you don't like the sound of 4-plexes replacing SFRs all over town, you might view that as reassuring, if ~95% of single-family lots would not be redeveloped. No parking? It will be very interesting to see how the "parking loophole" in SB 9 works within Manhattan Beach. If you've ever tried to build here, you know how requirements for on-site parking (covered and/or uncovered) can squeeze development plans. The state's prior ADU rules chipped away at parking requirements that had been a barrier to adding units. Can SB 9 really mean new, denser developments require only one space per unit, or none if within a half mile of "public transit?" Heck, the city's only 2 miles square, and people do actually have cars.

No parking? It will be very interesting to see how the "parking loophole" in SB 9 works within Manhattan Beach. If you've ever tried to build here, you know how requirements for on-site parking (covered and/or uncovered) can squeeze development plans. The state's prior ADU rules chipped away at parking requirements that had been a barrier to adding units. Can SB 9 really mean new, denser developments require only one space per unit, or none if within a half mile of "public transit?" Heck, the city's only 2 miles square, and people do actually have cars.